Dust & Diagrams: Patents, Prototypes, and the Birth of the Modern Typewriter

There's a particular scent associated with old technology: a mixture of oiled metal, dried ink, and the faintest whisper of forgotten lives. It’s the smell I remember most vividly from my grandfather’s workshop, a space filled with discarded clocks, radios, and a battered Underwood typewriter. He wasn’t a collector, not really; he was a fixer, a mender. And that Underwood, stubbornly refusing to produce anything legible, became his latest obsession. He’s gone now, but the memory of him wrestling with that machine, tracing the intricate mechanisms with his calloused fingers, remains a potent reminder of the ingenuity and perseverance woven into the history of typewriters. It’s a history far more complex and fascinating than most imagine, a story of furious competition, ingenious design, and the surprisingly human drama behind an object we often take for granted.

The impulse to mechanize writing goes back surprisingly far. Early attempts, from the 17th and 18th centuries, were largely novelties – complex contraptions designed more to impress than to truly assist in the writing process. However, the mid-19th century saw a burst of innovation, fueled by the burgeoning industrial revolution and a growing demand for more efficient office practices. The need to produce legible documents quickly and consistently ignited a fervent race for patents and a whirlwind of prototypes.

The Patent Wars Begin: From Davenport to Sholes

While numerous individuals contributed to the typewriter's evolution, the generally accepted "father" of the modern typewriter is Christopher Latham Sholes, along with his partners Carlos Glidden and Samuel W. Soule. Their initial design, patented in 1868, was crude but functional, a quirky arrangement of levers and a type bar that struck the paper from below. However, Sholes’s wasn’t the first. Before him, a number of inventors, most notably William Austin Burt with his "Typographer," had attempted to create similar devices. Burt's machine, while a fascinating early effort, suffered from a number of limitations. The ensuing years were marked by a tangled web of patent claims, cross-licensing agreements, and legal battles – a true patent war. The persistent mechanical challenges and relentless pursuit of perfection also created a certain aura of solitude and focus for those involved; a solitary dedication reminiscent of what some might describe as the typist's reverie – a world apart, lost in the rhythmic clatter of keys.

The story is filled with frustrating details. For example, early typewriters often had their type bars striking from below the paper, creating a messy, hard-to-read result. The initial designs were also incredibly difficult to operate. Sholes’s early machines, famously, typed from left to right – the exact opposite of modern practice. This seemingly minor detail stemmed from the limited space on the initial platen and proved incredibly inconvenient, leading to a lot of back-and-forth movement across the page. The struggle to get the design right was a constant process of trial and error, a relentless pursuit of a solution that was both practical and commercially viable.

The QWERTY Conundrum: Necessity or Conspiracy?

Perhaps the most enduring legacy of the early typewriter era is the QWERTY keyboard layout. Popular myth attributes its peculiar arrangement to a deliberate strategy by Sholes to slow down typists, preventing the type bars from jamming. While this tale is widely circulated, the reality is more nuanced. Early typewriters, with their closely spaced type bars, did suffer from jamming when frequently used keys were pressed in quick succession. Sholes, therefore, consciously separated commonly used letter combinations to reduce this issue, but not necessarily to sabotage typists. The layout was a pragmatic solution to a mechanical problem, and it stuck – despite numerous attempts to create more efficient alternatives. Today, the QWERTY layout feels almost anachronistic, but it remains the standard, a testament to the inertia of established technology. The quirks of these early machines, the strange characters that arose from the imperfect printing – they almost possess a certain literary quality, evoking the feeling that a ghost in the font might be present, imbuing each document with a unique and subtle charm.

The Remington Era: From Sewing Machines to Typewriters

In 1873, Sholes sold his patent to Remington and Sons, a company renowned for manufacturing sewing machines and firearms. This marked a pivotal moment. Remington had the resources and manufacturing expertise to transform the cumbersome prototype into a commercially successful product. Their initial typewriters, initially marketed as “Type-Writers” (the hyphen eventually dropped), were essentially modified sewing machines, complete with the familiar treadle mechanism. This design choice, while unconventional, provided a degree of familiarity and appeal to potential customers.

The early Remington typewriters were a significant improvement over Sholes’s original designs, but they still had limitations. They were loud, bulky, and relatively slow. However, they represented a critical step forward in the mechanization of writing, and their success paved the way for further innovation. The company also introduced the use of the lowercase letter on the underside of the type bars, a clever solution that doubled the number of characters that could be printed.

Craftsmanship and the Enduring Appeal of Vintage Typewriters

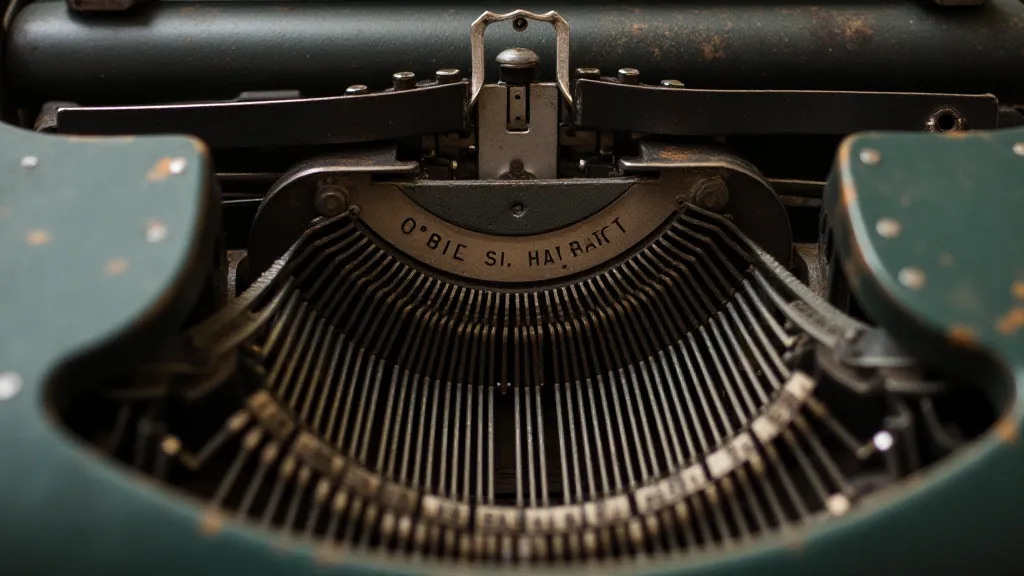

Examining a vintage typewriter today, even a well-worn example, reveals a remarkable degree of craftsmanship. The intricate mechanisms, the precisely engineered type bars, the sturdy construction – these are testaments to the skill of the engineers and machinists who built them. My grandfather, with his knack for fixing things, appreciated this craftsmanship deeply. He understood that these machines were more than just tools; they were intricate works of engineering, built to last. The gentle fade and imperfections on the ribbons themselves speak volumes about the passage of time; a poignant echo of ribbons of time, each color and imperfection a subtle reminder of the stories they're helped to tell.

The rise of digital technology has undoubtedly diminished the practical need for typewriters. However, they haven't disappeared. A renewed appreciation for analog tools, for the tactile experience of physical objects, has led to a resurgence in interest in vintage typewriters. Collectors are drawn to their aesthetic appeal, their historical significance, and the unique character they impart to written documents. The clatter of the keys, the satisfying impression on the paper – these are sensory experiences that cannot be replicated by a computer keyboard.

Restoration and Collecting: A Window into the Past

For those interested in exploring the world of vintage typewriters, there are several avenues to pursue. Restoration can be a rewarding endeavor, bringing a neglected machine back to life and preserving a piece of history. Even simple cleaning and lubrication can significantly improve a typewriter's performance. Collecting, of course, offers another appealing option, allowing enthusiasts to amass a diverse range of models, each with its own unique history and design. Whether you're drawn to the elegance of an Underwood, the robustness of a Royal, or the quirky charm of a Smith Corona, the world of vintage typewriters offers a fascinating glimpse into a bygone era – an era of ingenuity, perseverance, and the relentless pursuit of a better way to write. The missing keys, the faded lettering, the imperfections on the casing – these aren't blemishes; they're stories waiting to be uncovered. Imagine the documents these machines have produced, the letters and poems that have been crafted on them. The history isn’t just about the inventors and manufacturers; it’s about the countless individuals who used these machines to communicate, to create, and to leave their mark on the world. The absence of certain characters can create intriguing gaps, suggesting untold narratives and hinting at the unique history of each individual machine – the very essence of what it means when you encounter the imprint of absence.