Beyond the Monospace: The Search for Personality in Mechanical Typography

The rhythmic clatter of keys. The crisp impression on the page. The satisfying *thunk* as the carriage return signaled completion. For generations, the typewriter wasn't merely office equipment; it was a portal to creation, a tangible link between thought and expression. And yet, within the seemingly uniform world of monospace fonts, a quiet rebellion bloomed – a persistent search for personality, a yearning to inject the human touch into a machine designed for efficiency. It’s a search that mirrors our own, doesn't it? The desire to leave a unique mark, to differentiate ourselves in a world striving for standardization. Think of antique accordions, each worn with the echoes of a thousand melodies, each key subtly different in tone and touch – a world away from the mass-produced instruments of today. The typewriter, in its early days, held a similar promise of individual expression.

The story begins, of course, with the realization that creating a machine to reliably reproduce written text was not a simple task. Numerous inventors tinkered with the idea throughout the 19th century, but the generally accepted “father” of the modern typewriter is Christopher Latham Sholes, whose design, initially marketed by E. Remington and Sons (yes, the gunmakers!), debuted in 1873. These early machines were wonderfully clumsy, loud affairs. They typed only in uppercase, a consequence of the design limitations of the typebars, the small metal arms that struck the paper. The uniformity was relentless. Everything looked… institutional. But even within this rigid framework, ingenuity found a way.

The Limits and Longings of Monospace: A Shift from Script to Steel

The dominance of the monospace font wasn't a conscious design choice meant to stifle creativity; it was largely a byproduct of the technology. Each typebar had to be precisely positioned to strike the platen squarely. Variation in font styles – bold, italic, different sizes – would have required an exponentially more complex system of levers and typebars, a practical impossibility for the early machines. Early adopters, largely business owners and clerks, were primarily concerned with speed and legibility, not artistic expression. The emphasis was on producing clean, consistent documents, eliminating the personal flair of handwriting. The transition from elegant, flowing handwriting to the more mechanical efficiency of typed prose represented a significant cultural shift—a moment explored in greater detail on our page dedicated to “From Script to Steel: The Transition from Handwritten Documents to Typed Prose.”

Yet, the human spirit resists uniformity. Writers, particularly those involved in the burgeoning fields of journalism and literature, felt the constraints keenly. They sought ways to circumvent the limitations, to imprint their personality onto the typed page. Early techniques were surprisingly resourceful. Some writers learned to subtly manipulate the typewriter’s keys, creating minute shifts in the alignment of letters, a form of unintentional or deliberate “jitter” that added a certain character to the text. Others experimented with the pressure applied to the keys, altering the depth and darkness of the impression.

The Rise of Font Variations: A Subtle Revolution

As typewriter technology advanced, so too did the possibilities for variation. The introduction of lowercase letters, a significant milestone, began to chip away at the relentless capitalization. Then came the shift to "universal" typefaces, which incorporated lowercase letters, numbers, and punctuation into a single font cartridge. But the most significant development was the advent of "shifted" fonts – fonts with multiple typefaces accessible through a lever or selector. These weren’t true variable fonts in the digital sense; they were physical, mechanical arrangements of typebars, but the effect was transformative.

The Underwood No. 5, introduced in 1900, was revolutionary. Its curved design freed up space for a front-mounted keyboard, and crucially, it offered a limited range of font variations – bold, italic, and a couple of distinctive “special” fonts. Suddenly, writers could subtly alter the appearance of their prose, lending a degree of stylistic individuality previously unattainable. Authors like Ernest Hemingway, known for his concise and minimalist writing style, likely appreciated the ability to subtly differentiate the appearance of certain passages. Think of the possibilities for a poet – a delicate italic for a tender verse, a bolder typeface for a stanza of resolve.

Beyond the Machine: The Human Touch and the Rhythm of Creation

Even with the introduction of these limited font variations, the typewriter remained a mechanical tool, an intermediary between thought and the written page. The true personalization came not from the machine itself, but from the skill and artistry of the typist. Skilled operators learned to mimic handwriting styles, employing a combination of key pressure, carriage adjustments, and even subtle manipulations of the ribbon to achieve remarkable effects. The touch typist, able to anticipate the mechanics of the machine, was highly prized – their output cleaner, faster, and more expressive. The very *rhythm* of creation, the cadence of the keys, became a form of personal expression. For those fascinated by the psychology of this rhythmic interplay, we’re exploring that very theme further on our page, “Echoes in the Carriage Return: The Psychology of Typewriter Rhythm.”

The rise of carbon paper further complicated – and enriched – the process. Multiple copies could be created with a single typing, enabling writers to experiment with different impressions and effects. The “ghosting” of the carbon copies, the faint impression of the characters bleeding through, became a characteristic feature of the era, a tangible reminder of the collaborative effort between writer and machine. The mechanical complexities of the early typewriter were often a source of frustration but also fostered innovation. The inventors and engineers who labored to bring these machines to life were grappling with patents, prototypes and the very birth of a new era. Further exploration of that historical context can be found on our page dedicated to the intricacies of early typewriter development.

Collecting and Restoring: Preserving a Legacy of Innovation

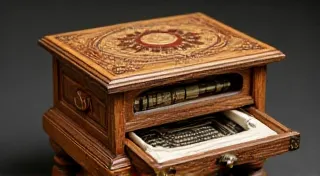

Today, antique typewriters are enjoying a resurgence in popularity. They are cherished not only for their aesthetic appeal – their elegant curves, their intricate mechanisms, their clattering charm – but also for the historical significance they represent. Collectors seek out rare models, original ribbons, and even carbon copies, preserving a tangible link to a bygone era. Restoring these machines is a labor of love, requiring patience, mechanical skill, and a deep appreciation for their craftsmanship. Finding original parts can be a challenge, but the satisfaction of bringing a silent relic back to life is immeasurable.

More than just collecting, restoring these machines is about preserving a part of our cultural heritage. They represent a time when writing was a more deliberate, more tactile process. They remind us of the human element in creativity, the quiet satisfaction of transforming thoughts into words, one clattering keystroke at a time. The story of how these machines spread, enabling the dissemination of ideas across geographical boundaries, is a fascinating journey in itself.

The path of the typewriter's journey wasn’t always smooth. Early models often relied on intricate and somewhat fragile mechanisms. Understanding the development of these machines required careful study of patents and prototypes, revealing the ingenuity and the challenges faced by the inventors of this transformative technology. If you'd like to delve deeper into the history and innovation behind these machines, we invite you to explore the fascinating origins of the modern typewriter on our page dedicated to “Dust & Diagrams: Patents, Prototypes, and the Birth of the Modern Typewriter.”